In 1969, American public television launched a children’s program called Sesame Street. Set in a fictional neighborhood in New York City, it was the main show I watched when I was little. There was always something for the parents to relate to, also, and in the early 1970s that still included singers from the folk era. I learned about the letter E from Buffy Sainte-Marie, a recurring guest, and heard Judy Collins sing her composition “Fisherman’s Song.”

I always associated my mom, Groovy Gracie, with Judy Collins, and it’s easy to see why. They each had a clear soprano, and Collins’s covers of Joni Mitchell songs were among Groove’s all-time favorites, including the famous “Both Sides, Now.” Wildflowers was one of the records she passed on to me, along with Simon & Garfunkel’s. Judy Collins is a Christian whose version of “Amazing Grace” is among the treasures of national significance at the Library of Congress.

It’s less obvious why I would associate Groove with New York, a city we never visited together. When I was growing up, New York was this exotic neighborhood on Sesame Street, where people rode buses and crossed at “Walk” lights, which I had never seen. But last week T. and I spent a couple of days in New York, and I spent most of that time thinking about Groove.

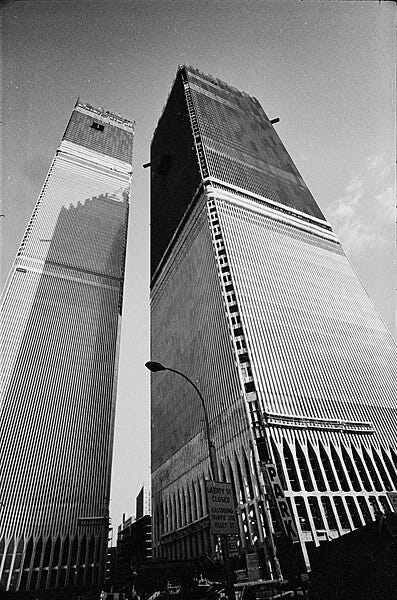

It may have been partly because this was our first time back in the U.S.A. since last Thanksgiving (in fact, we changed planes in New York in January/February, but that was just a transfer to South America and we never left the airport). It may be because I recently heard the story of how, before I was born, my mom and dad visited a cousin she’d grown up with and her husband, who were then in New York. The four of them had a great time, seeing Man of La Mancha on Broadway and hanging out in the city—and now, all of a sudden it seems, three are gone. I enjoyed imagining Groovy Gracie, before she was my mom, as one of those young people, on the streets of Manhattan before the World Trade Center was even built.

Or maybe it was the songs of Simon & Garfunkel that kept coming into my head, as T. and I walked past places mentioned in their songs: the Central Park Zoo, the 59th Street Bridge (“Feelin’ Groovy”). Groove loved those records, and as a college student, once wrote a paper about old age as viewed through the songs of those young men.

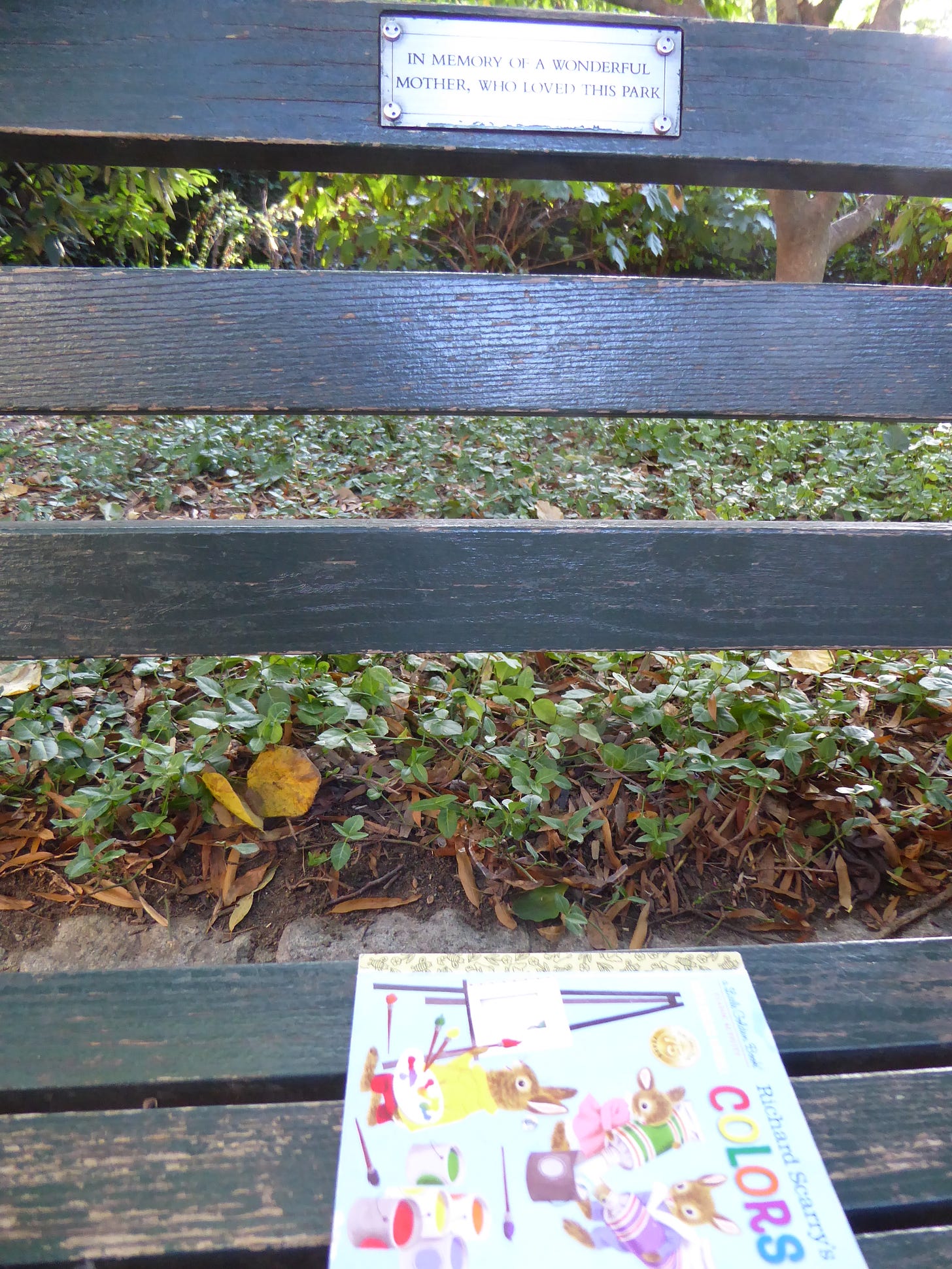

Old friends, old friends

Sat on their park bench like bookends

A newspaper blown through the grass

Falls on the round toes

Of the high shoes of the old friendsOld friends, winter companions, the old men

Lost in their overcoats, waiting for the sunset

The sounds of the city sifting through trees

Settle like dust on the shoulders of the old friendsCan you imagine us years from today

Sharing a park bench quietly?

How terribly strange to be 70 🎵

I wish I had that paper.

T. and I packed a lot into 48 hours. We went up to the outdoor observation deck of the Empire State Building (1931), something I’d never done before, probably because it was too expensive. (Guess what? If you put something off for that reason, it will be even more expensive next time.)

Groove was a teacher, mostly of kindergarteners, and so had a special insight into how to communicate with little kids. It was something she and I talked about many times, long after I’d outgrown Sesame Street. For instance, when the actor who played a beloved character died, the makers of “Ses,” as she called it, made a show trying to explain to children what had happened to the character. To tell them about death, but in an age-appropriate way. They approached it through the character of Big Bird, who (although he’s eight feet tall) is supposed to represent a child aged about six. I was much too old to watch the show then, but I remember my mom telling me about it.

One aspect of the show that bothered me as a child, though, had to do with Big Bird’s friend, Mr. Snuffle-upagus. “Snuffy” only appeared to Big Bird when no other characters were present, which led all the adults on the show not to believe in his existence. As an adult, I understand that this was supposed to represent the imaginary friend that a child has. The problem was that as children watching the show, we could all see Mr. Snuffle-upagus; he was as real as Big Bird. It bothered me that none of the other characters believed Big Bird when he was clearly telling the truth. Except for Buffy, who, although she never saw the imaginary friend either, sang a song to Big Bird about believing him anyway.

When I say it bothered me, I mean that I got my mom to help me compose a business letter to Sesame Street—she must have typed it for me. Imagine my satisfaction, years later, when she reported back that the show had switched tactics, in response to a rising awareness of child abuse (nothing to do with my letter; it was the ’80s by then). Thankfully, I’d known nothing about abuse as a child. But I remember the conversation when my mom told me Sesame Street no longer wanted to send the message that adults would not believe children, who might have something important to tell them.

Fifty years after the show’s premiere, New York City officially named the stretch of 63rd Street west from Central Park to Broadway “Sesame Street.”

If “Ses” was one bookend to my knowledge (from a distance) of New York, the other was surely the area of Lower Manhattan destroyed on September 11, 2001. T. and I visited the new museum that stands on the site of what used to be the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

We’d been to the site before, and seen the memorial pool. But this was the first time we’d been in New York since the museum opened. T. soon found it too much to be in the very footprint of the building. I, however, felt the need to read all the stories.

Not about the attacks themselves. I have written my memories of September 11; to this day I am stunned by the tactical audacity of the terrorists, and yet I remember what air travel was like before that terrible day. How my college bulletin board would advertise airline tickets you could swap, to fly to Boston instead of New York—you didn’t need ID to get on a domestic flight in those days. How I always used to carry my Swiss Army knife on board planes, mostly to slice open the little packages of peanuts. (Even peanuts are now considered dangerous.)

In the museum, I wanted to see objects like the squeegee handle that someone carried up in an elevator to clean windows that morning. When the airplane hit the tower, he and the others in the elevator took turns using his squeegee until eventually, they could pry the doors open—and escape down the stairs.

Part of the reason I kept thinking of my mom, of course, was the enormous sense of loss: People died here. But it was also because, like everybody else, on September 11 I called my nearest and dearest just to hear their voices. And that meant my parents. I’d have said “Hi, Groove,” because that’s what I always said when my mom picked up the phone.

We’d have tried to find words for what was going on. The memory of September 11 brought me back to a child talking to her mother, never mind age and time. We talked on the phone to comfort each other, but there was no comfort to be found. That day, I remember the absolute disgust in her voice when she talked about how the passengers on the hijacked airplanes, the crew, were treated. To the terrorists, she said, “they were just fuel.” People, treated as if they were nothing more than fuel to burn a building.

I’m not going to spend the rest of this post on the September 11 memorial. But I thought about my mom, and calling my mom that day, and what she said to me. Because in that museum were groups of schoolchildren walking around, and young adults even old enough to vote, who were not yet born on that day. It was history they were discovering, but to us, it’s living memory.

So. What else did we do in New York? Well, we ate. There was a bakery literally across the street from our Airbnb that was opened by Hungarian immigrants in 1916. They made very good coffee and, I can attest, a bagel with everything that was also delicious. I also had latkes, something for which yes, Groove, gave me a recipe that I still have (a legacy of the year our pediatrician’s son was in her class, and his mom introduced the rest of the kids to Hanukkah).

And of course, hot dog stands were everywhere. Though like the Empire State Building, hot dogs are more expensive these days.

We were staying in an old walk-up apartment on the Upper East Side. Good things I can say about it are that it was in the rear, so remarkably quiet, and the location was great.

We spent a lot of time in nearby Central Park.

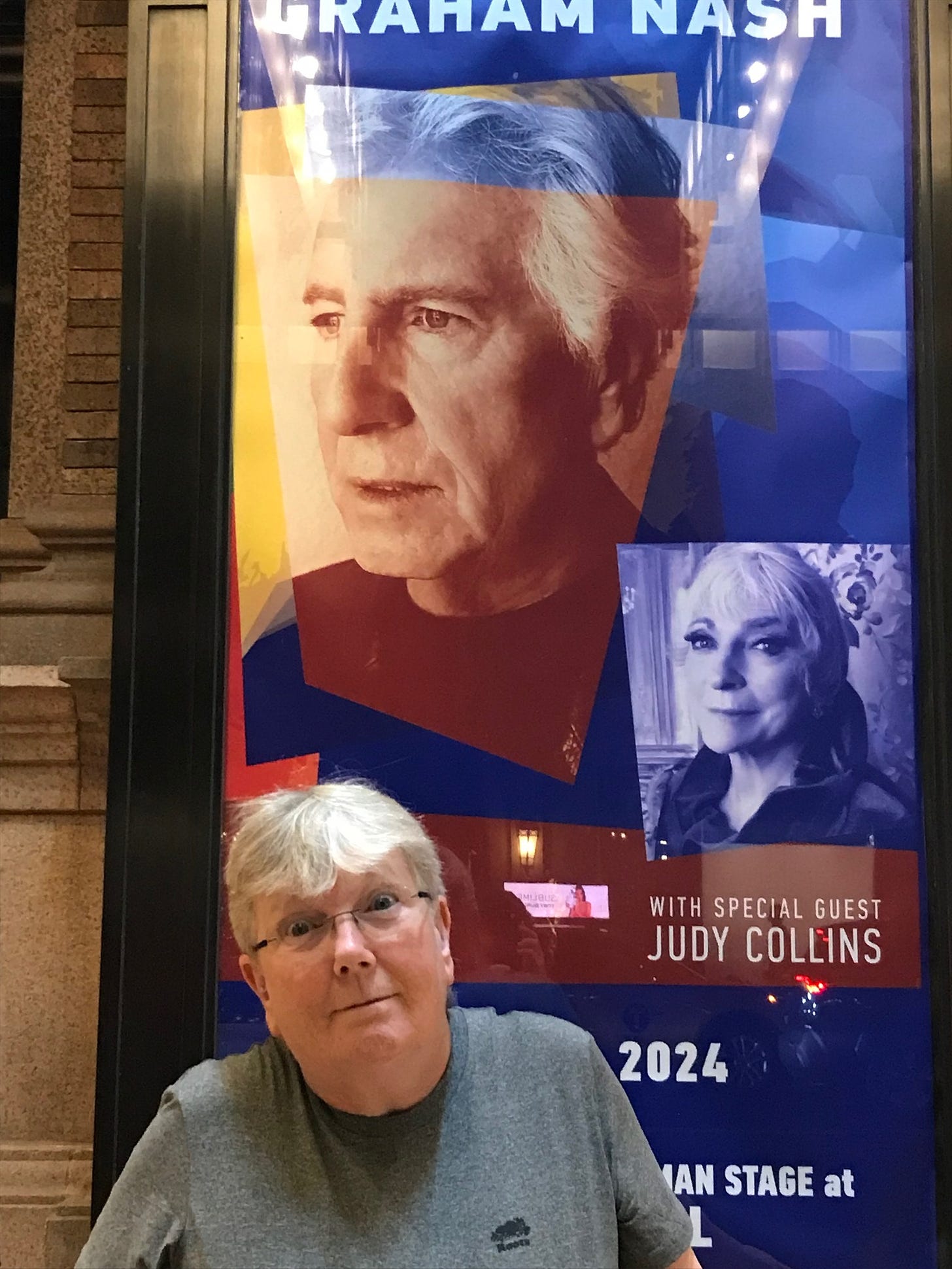

But after a full day of exploring all this came the highlight of our trip and the reason I’d wanted to go to New York. Some months ago, my mom’s cousin Rick had alerted me that Graham Nash was going to be playing at Carnegie Hall, featuring his friend and special guest, Judy Collins! I noticed that on the date we were only going to be across Lake Ontario, not the Atlantic Ocean as usual. Groove had once pointed out a Judy Collins concert in my hometown, many years earlier, but unfortunately that one didn’t overlap with my being home, or we would have gone to see her together.

When Judy Collins stepped out onto the iconic Perelman Stage at Carnegie Hall, and started singing “Both Sides Now,” I could not contain my emotion. I had to close my eyes and focus on the music, thinking of Groove and what she’d say about the song. “Youth in a nutshell,” she’d described it. Whereas Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends is an album by young men looking forward at old age, here “Both Sides Now” was being sung by an old woman, looking back at the other side of life.

Yes, Judy Collins is old, but she didn’t sound it. I wasn’t aware until I looked her up later that she’s actually 85! Years ago I heard her on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz, and she talked about how she trained with a vocal coach and exercised her voice, no longer taking for granted what gravity could take away from her. When I closed my eyes and listened to Judy Collins last week, she could have been singing in the ’90s, or the ’60s.

She talked to the audience about her own time living in New York (one street over from ours), meeting Leonard Cohen, singing his song “Suzanne.” She remembered first visiting Carnegie Hall and seeing the Weavers there—the groundbreaking (and blacklisted) 1950s group comprising Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman. The Weavers had an early hit with Leadbelly’s “Goodnight, Irene,” and Hays and Seeger wrote another all-time great song that Groove and I always sang together: “If I Had A Hammer.”

T. was with me the whole time Judy Collins was on stage, but she was there more for the building than for Judy. Her fondest association with Carnegie Hall was Billie Holiday. Nonetheless, at the end of Collins’s set T. had this to say: “She’s a game old bird, I’ll give her that.”

Judy Collins was truly incredible. She accompanied herself on guitar and, at one point, even on piano. And she made this joke about an atheist in a morgue: “All dressed up and no place to go.”

Of course, she could not leave the stage without performing her greatest hit: Stephen Sondheim’s “Send In The Clowns” from A Little Night Music. Collins made the song her own in the ’70s, and it sounded as good as ever when she sang it. But I have to admit it brought to mind one other Groove memory: a story she told about a wedding she’d attended, around the time “Send In the Clowns” was particularly popular. Someone had made the unfortunate decision to have the pianist play it just as the mother of the bride came up the aisle. How my mom laughed and rolled her eyes when she told that story!

Below is a picture of Judy Collins performing on what turned out to be Groovy Gracie’s last birthday. I can assure you Judy looked exactly the same last Tuesday night:

At the end of the following video (which I hadn’t seen since it originally aired), a Muppet fisherman is heard to say “You’re just like my mother; you sing real pretty, pretty lady!” That is how I felt, in Carnegie Hall, when Judy Collins had us singing along together to “Goodnight, Irene” and Pete Seeger’s “Where Have All The Flowers Gone”🎵